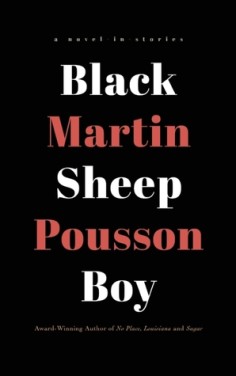

Black Sheep Boy: Against All Odds – Author Post + Video Reading by Martin Pousson

Art that belongs to everyone in general belongs to no one in particular. It has no more conviction than the wind and no more permanence than the water. With Black Sheep Boy, I set out to write a book not for every reader but for a particular one: the cultural queer, the sexual queer. I write for the outcast and the misfit, and I write for those who want to see the world in ways that are angular and irregular, uneven and odd. In the thirteen stories that accumulate into a novel, I write not to comfort and console but to provoke and perturb, for I believe at its best, fiction is an act of revolution. Fiction shouldn’t reflect the world merely as it is but also as it might be. A novel is not a flat one-way mirror but a rippling pool of invention, distortion—and of refraction more than reflection. “Tell all the truth,” Emily Dickinson says, “but tell it slant.”

wind and no more permanence than the water. With Black Sheep Boy, I set out to write a book not for every reader but for a particular one: the cultural queer, the sexual queer. I write for the outcast and the misfit, and I write for those who want to see the world in ways that are angular and irregular, uneven and odd. In the thirteen stories that accumulate into a novel, I write not to comfort and console but to provoke and perturb, for I believe at its best, fiction is an act of revolution. Fiction shouldn’t reflect the world merely as it is but also as it might be. A novel is not a flat one-way mirror but a rippling pool of invention, distortion—and of refraction more than reflection. “Tell all the truth,” Emily Dickinson says, “but tell it slant.”

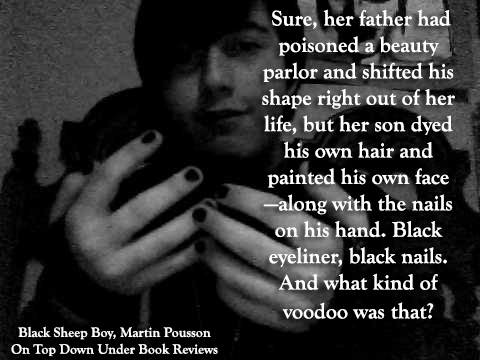

Black Sheep Boy slants its truth with an outsider boy in an outsider culture, a mixed-race queer boy in a mixed-up odd land where bayous run under houses, where trees grow out of water, where moss grows even on rolling stones, and where people venerate the Virgin Mary and practice voodoo in the same room and at the same time.

Black Sheep Boy slants its truth with an outsider boy in an outsider culture, a mixed-race queer boy in a mixed-up odd land where bayous run under houses, where trees grow out of water, where moss grows even on rolling stones, and where people venerate the Virgin Mary and practice voodoo in the same room and at the same time.

The outsider culture of Louisiana Cajuns arose from a forgotten chapter in US history, a pre-revolutionary Great Upheaval in which a mixed-race people were subjected to the horror of the largest mass deportation and mass diaspora in the western hemisphere but then never bothered to write down that history for fear that it would become too fixed and too real. The Cajuns, a French-speaking people mixed with various tribes, laughed furiously to jokes about suffering and danced manically to songs about severance. They knew no codified language, no standard currency, and no racial hierarchies until forced into formal US education in the twentieth century, when they subsequently created all manner of false hierarchies, including arbitrary divisions of color from Cajun to Creole to Sabine, from quadroon to octoroon, and when they created new arbitrary divisions in gender, labeling any non-cisgender boy a sissy, a fairy, a Jenny Woman, a puss. As with too many episodes in history, those who were once subordinated as cultural radicals sought others to subordinate, especially sexual and racial outsiders. Yet in one way or another, everyone in the bayou land of Louisiana stood at a crossroads of gender identity and gender expression, and they stood in a crosscurrent of languages and ethnicities, all of which were constructs, that is to say all of which were—and are—myths.

Black Sheep Boy surveys that crossroads with counter-realism or magic realism, a mode of fiction that objects to reality, interrogates it, and finally moves what is subordinate into the main frame and what is subliminal into the forefront. The novel rejects cultural assimilation and gender normativity as the compromises that they are, and the novel rejects reality and realism as a manifestation of those compromised positions. After all, the goal of every story should not be to add to our knowledge but to relieve us of it, to grant us freedom from the known and reentry into the unknown, the marvelous, the mysterious, and the mythic.

Over the course of the novel, I revisit not only the historical traumas inflicted upon ethnic minorities but  also the all-too-current traumas inflicted upon gender and sex minorities: bullying and bashing, harassment and homicide. Returning to myth allows me to return to a realm of fiction filled with androgyny and sexual ambiguity, metamorphosis and gender fluidity. In this realm, the traumas of the novel ultimately lead to triumphs, as the cultural queers and sexual queers of the book find common cause. Their fight doesn’t end, though. Since inclusivity of all genders and cultures should not lead to political neutrality, acceptance of gender variance and cultural difference should not lead to sexual neutering. Whether in bedrooms or bars, there is no flinching at difficult sex in the book. All monsters are unmasked, and each reveals a human face.

also the all-too-current traumas inflicted upon gender and sex minorities: bullying and bashing, harassment and homicide. Returning to myth allows me to return to a realm of fiction filled with androgyny and sexual ambiguity, metamorphosis and gender fluidity. In this realm, the traumas of the novel ultimately lead to triumphs, as the cultural queers and sexual queers of the book find common cause. Their fight doesn’t end, though. Since inclusivity of all genders and cultures should not lead to political neutrality, acceptance of gender variance and cultural difference should not lead to sexual neutering. Whether in bedrooms or bars, there is no flinching at difficult sex in the book. All monsters are unmasked, and each reveals a human face.

In addition to the gothic setting of the Louisiana bayou land, the novel moves loosely through the Post-Stonewall Pre-AIDS era in a series of stories that alternate between the almost realistic to the fully magical, including local myths, regional legends, alternate histories, and personal fantasies that form less a coming-out novel and more of a coming-into. Various characters appear and reappear. In the thirteen stories, there’s a mixed-race Holy Ghost mother, a Cajun French phantom father, plus gender outlaws, drag queen renegades, and a rogues gallery of sex-starved priests, perverted teachers, and murderous bar owners. In the end, though, Black Sheep Boy is the story of one particular queer boy creating a new self against all odds in a very queer culture and a very queer place.

Kazza’s Review

Martin Pousson reading from Black Sheep Boy, and it’s pretty awesome…

I remember well how much Kazza enjoyed Black Sheep Boy. It’s a pleasure to have Martin Pousson stop by. I love the post and the video is fantastic.

Black Sheep Boy is amazing and this post is a bonus. That video reading is also an absolute favourite of mine – the passion and feeling, perfect.

LOVE this. I’ve wanted to read Black Sheep Boy since Kazzas review. This makes me want to read it more.

Thanks, Lauren, and definitely read it. Definitely 🙂