Blog-versary Author Post : Scott D Pomfret, Half a Man

Half a Man.

Scott D. Pomfret

A threadbare tongue, English hasn’t names enough for the multiple ways a single thing may be, or idiom to express the heights of grief, or madness, or joy, or cunning. A richer tapestry is in my mother’s native Irish. Case in point: English has no exact and apt and proper equivalent for the Irish word seanachie, a figure most prized in my mother’s literary and erudite family.

A threadbare tongue, English hasn’t names enough for the multiple ways a single thing may be, or idiom to express the heights of grief, or madness, or joy, or cunning. A richer tapestry is in my mother’s native Irish. Case in point: English has no exact and apt and proper equivalent for the Irish word seanachie, a figure most prized in my mother’s literary and erudite family.

A seanachie is an assembly: part storyteller, part soothsayer, part shaman, part shapeshifter, part witchdoctor, and part court jester, but each threaded with unreliability and mischief and maybe a dash of leering besides. For the average lout, things merely are what they are, and the world is a silent place, a grave monastery, where the scribbling and copying goes on apace. The seanachie’s world is riot. It’s studded with signposts and echoes and flashes of tomorrow. Everything is personal and has insistent meaning, and to a seanachie, a bowl of Cheerios is never exactly or only a bowl of Cheerios, but also has other surprising and delightful contents, if only he is sensitive to the shift of its shape.

Such sensitivity is receptivity; it’s neither more nor less than being the world’s “bottom,” and I was a “sensitive child” in the days before that term was widely recognized as a euphemism for homosexual. From the beginning, I yearned to be the discerning, spell-casting, prophecy-making seanachie from the Irish Faerie tales, and at age six, I triumphantly published my first poem, an interpretation (dare I say, translation?) of the song of humpbacked whales.

and I was a “sensitive child” in the days before that term was widely recognized as a euphemism for homosexual. From the beginning, I yearned to be the discerning, spell-casting, prophecy-making seanachie from the Irish Faerie tales, and at age six, I triumphantly published my first poem, an interpretation (dare I say, translation?) of the song of humpbacked whales.

Lauds followed publication; a certain six-year-old head swelled. Dizzy and defiant, I began to imagine that I was the source of stories and songs and prophecies, and due sole credit for them, when in truth words were and are but a gift and easily revoked. The seanachie is a recipient of (bottom for) grace; he is gifted, in the sense that honeyed words are bestowed on him, perhaps by Faeries, and not of his manufacture alone.

And so, for hubris, the gift was revoked from me. Between ages six and twenty, no further stories or songs were vouchsafed to me, however hard I tried to wrench them from my world. (I have a distinct and cringing memory of describing a “cloud purpling like a promise made years ago” in the prose of my sophomore fiction writing class.)

And yet still, I clung to the conception that I might yet be a seanachie, and there was certainly some evidence to support the claim. As I later wrote in my memoir Since My Last Confession, I hailed from a family of mismatched parts:

I come from a family of halfsies, botched starts and conflicting impulses. My paternal aunt became a nun, left the convent, married, and now ministers to alcoholics. My uncle started life as a man but is now a woman. (We call her “Auncle.”). My French Canadian side tempers my Irish half. My father was born a Protestant, but educated Catholic and served as altar boy. We take two steps forward and one back. We don’t always get it right the first time.

I was a football team captain; I was a secret cocksucker.

Seanachies, too, are inevitably many things at once: They tend to have a penchant for telling not only lies, but also inconvenient or ill-timed truths. They shift shape. They obfuscate. No strangers to fear, they compulsively tell stories to fill the time, to fill the void, to put off the inevitable, to ward off inquiry and throw them off the scent.

***

In my mother’s native Ireland, the seanachie is associated with the Faeries, who are also known as the Good People or the Sidhe. This race of immortal diminutive folks often described as fallen angels inhabit raths (forts) in the countryside of Ireland. They are fond of merriment, music, dancing, and, above all, tweaking the mortals’ vanities. In my forthcoming novel, The Hunger Man, I describe one of the Faeries as follows:

Fin Bheara was a wonderful and caustic host: a fallen angel, moody and insolent, neither good enough for heaven nor bad enough for hell, son of The Dagda and Boann, related to Lugh and Niamh and Crobh Dearg and Mananan mac Lir, and a lost older brother of Jesus himself, Fin could talk a blue streak, and the yarns he told of Heaven before the Fall were the best I ever heard. He never wanted energy for dancing or bedroom games, and his laugh always sent a shiver through me and put a uaill and scréach upon my lips that could be heard by every deabhal. Slender, salacious, and magnetic, Fin Bheara glowed through all his skin, adorned himself with hammered gold and bangles of a dozen treasure chests, and wore an emerald suit and red cap, and his handsomeness was three-quarters danger.

The Faeries are proud and easily offended, and they know grudges well and hoard them like gold. When a Faerie is vexed, the milk curdles, the butter refuses to come, the spionan drops its leaves rather than yielding fruit, plantstalks’ necks break, the pigs grow sorry and thin, the praties are mush and few, tempers are rash, kindness rare, and generosity all bound up in string. Even today, we all know the character type the Faeries represent, and it’s worth keeping on their good side.

The association with Faeries was apt, of course: I was no Faerie, but certainly a fairy. In my head, I felt as exotic and queer as the Queen of Sheba. Still, I had the gift and curse of being able to pass as straight (see above: varsity football captain) and took every advantage of the prerogative.

On a college roadtrip to Mardi Gras in a rented RV the odometer of which we mercilessly tampered with to save us mileage charges, I shouted for the girls to show their tits when I was with my friends, and we manly men hefted parked cars to the curb so the RV could pass through the Quarter’s cramped streets, and we chums vied with one another to consume all the intoxicants New Orleans had on offer.

tampered with to save us mileage charges, I shouted for the girls to show their tits when I was with my friends, and we manly men hefted parked cars to the curb so the RV could pass through the Quarter’s cramped streets, and we chums vied with one another to consume all the intoxicants New Orleans had on offer.

Yet whenever I could, I became “lost” in the crowd. I got saved by the street preachers and haunted the streets outside the gay bars and wondered what magic transpired within those fairy raths. Fire-setting gazes lit on me and flew off again like so many larks. Details snatched at my attention and held it fast: ribbons and Krewe’s masks and colored beads hanging on tree branches and boys with hats cocked at odd angles and mounds in their pants.

I almost gave myself away. In a sex shop off Bourbon Street, I bought one of my friends and travelling companions a wind-up plastic penis that clacked like a set of false teeth. When I set it to work on the RV’s table, my friend’s horror was genuine: it became apparent that, even as a gag, boys do not give other boys such gifts. Such curses. My own teeth chattered excuses to the clattering penis’s tune. I had no instinct for straightness. I was making shit up. I was panicked. I was guessing.

Despite the perils of exposure, I took mischievous delight in deception: by day, I passed myself off as conservative and straight: successively a high school football coach, corporate lawyer, government prosecutor, hedge fund compliance officer. By night, I wove a less conventional tale that translated into the gay-fueled fairy tales that again began to flow from my keyboard. Even as I “passed,” I loved to tweak the denizens of my day life with our differences: the slightly off, the missed expectations, whatever made my bros feel I was not one of them.

The constant shifting of shapes wasn’t the best strategy for making friends, and there were many who figured me out. My friend from the RV was one who felt deceived. Dry wraith, matchstick thin and as likely to be set afire with a little friction, a riven bloom on a restless branch, he had no patience for women, or the weak, or the half or the fraction of a man (which to him amounted all to the same thing). Not that he had no heart himself or that it was small, but it was full of anvils. He loved to be unreasonable. His wrath was like the Faeries’ and the grudge still stands today, not so much over the clattering penis, as over the extended refusal to come clean.

But the genius of the seanachie is that he actually likes to be alone. He likes spending time staring at things others have stared at and seeing more. He likes his reticence to be perceived as mystery, and if someone calls bullshit, he moves stealthily on to the next crowd, among whom he tried again, perversely, to be alone.

***

Seanachies, it should be clear, don’t make the best boyfriends. Inconstant, incapable of telling appropriate white lies, full of mischief, spreaders of cloaked truth, dissatisfied with the plain and direct and always looking for a richer tapestry, they can wear a man out. The seanachie says what comes into his mind, and his partner is rightly suspicious he doesn’t mean them. The seanachie renders a blessing and, while his man may join the chorus, he’s uncertain what’s been asked for. The seanachie often reveals unwanted glimpses of what he claims is the boyfriend’s future. He holds the boyfriend at arm’s length with mischief, but binds him close with a heartfelt song.

Moreover, like the Good People of Irish tales, a seanachie tends to prefer what’s new and pretty. He can’t get serious when needed. He cries maudlin tears when a boyfriend needs him to be tough. He compulsively spins stories and not one of them exactly true, though they have a sort of queer truth to them. Suspicious, susceptible, sentimental. You know the type. Thank God for sisters who have the grace to see the seanachie in the best light.

Even now, I admit, I’ve woven a few lies into the weave of this essay. No, let’s not call them lies, which offends. Let’s call them strategic omissions or stretches of the truth. Let’s call them mischief, and remember, charitably, that mischief is the flip side of shyness, a shiny coin often tossed.

***

There’s a delight in deception that animates every fiction writer and also a streaker’s thrill in the flash of momentary exposure. No matter how much a writer repeats the mantra that he’s uncovering a different kind of truth, he’s at heart a clever liar dissatisfied with language’s threadbare cloth and made cold by it.

Writers become drunk with mischief and magic. Stories are inherently unreliable. Received as they are from another source, rather than generated within, they often don’t go where the writer wants; they become something other than what they seemed to be or they prove a curse; their authors tease and disappoint.

When the Faeries finally gifted a few, average stories to me — many gay-themed, but the first oddly published in a straight guy’s girl-next-door pornographic magazine — people in the my conservative world collectively frowned.

Many asked, “Where did that idea come from? It’s so not like you.”

“It’s just a story,” I used to say, shrugging. “That’s not me.”

But it was me, as my friends in the gay world know. As other writers know. I do sometimes see what’s hidden beneath the surface, even if I can’t always say it plainly. I pick from shadows the dun-colored birds, and detect among the trees animals that take color from bark, or see the hare crouching in the fields, or eye the fish in a flicker under a green bank, or know the devil from the mortal men among whom he hides. I write it up in the guise of fiction. The story is my rath.

see what’s hidden beneath the surface, even if I can’t always say it plainly. I pick from shadows the dun-colored birds, and detect among the trees animals that take color from bark, or see the hare crouching in the fields, or eye the fish in a flicker under a green bank, or know the devil from the mortal men among whom he hides. I write it up in the guise of fiction. The story is my rath.

Why not instead just say exactly what I mean in workmanlike nonfiction prose?

It’s fundamentally a lack of trust. The future casts shadows backward if you’ve eyes to see them. Faeries can turn a man into a solid object, and I’m always anxiously waiting on objects to turn back and prove themselves as what they truly were to begin with. Imagine mistrusting a barstool for fear it instantly transforms to the one-eyed ogre it always was. I live on edge. Accordingly, I dissemble. The seanachie does not trust, therefore is he untrustworthy.

Interestingly, if ever I encountered a disdain equivalent of the straight bro who discovers you were a secret cocksucker all along, it’s the disdain of those who pride themselves on limiting their reading only to non-fiction, which signals contempt for the seanachie’s arts and parts and a yearning for the words to more exactly represent a simple reality.

For the seanachie, bald truth is both too easy and simultaneously terrifying.

***

Nevertheless, integrity is the seanachie’s wet dream. Or, at least, he tells himself this is what he wants: to weave together the disparate parts. To introduce them at a grand dinner party of the soul and by mutual shared experience induce them to see they are not that much different from one another. For once to speak plainly and earnestly. To be thought a mensch (another word defying translation!). A real man. To be reliably exactly who he is and no shapeshifters need apply.

But a seanachie is never one thing. Never pure. Never all this. Never 100% that. If actually uncorrupted, he is keenly aware he is infinitely corruptible. Don’t blame English for being word-poor, I suppose. How could a single name or word capture the seanachie’s enchantments? We are all poor and rich at the same time, and the seanachie is a moving target.

***

In The Hunger Man, I created a character called Ciaran Leath, a kinder, better sort of seanachie. Here is how Ciaran describes himself:

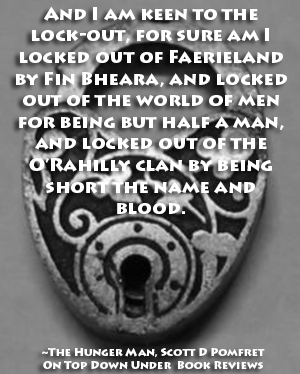

A mere bone chip of a baby, I entered the world on Candlemas Day with a head of golden curls that turned black as blindness after just seven days and then again flame-red seven days later. Left for dead, I was named by boys who found and knew me well: Ciaran Leath, they called me, because ciaran means “dark” and leath is Irish for “half.” I am the dark half. I am twilight: half day and half night, half this and half that, half woman and half man, half Catholic and half pagan, half here and half one foot in the OtherWorld, half human and half Faerie, a cross between the Good People and the rest of us.

Ciaran Leath is defiantly himself and, fond of boys, not much skilled at either keeping chaste or keeping a secret — a volatile chum, indeed, but unbroken by his multiplicity and disparate parts, an unashamed bag of elbows and knees.

Half a man may sound like a stingy gift, but it actually reflects an uncommon generosity, and Ciaran Leath is my current dream. Neither pure nor whole, not quite the sum of the parts, this is the seanachie’s awkward jig: to become what he is, and what he is always changing and shifting its shape and drifting maddeningly out of reach.

#

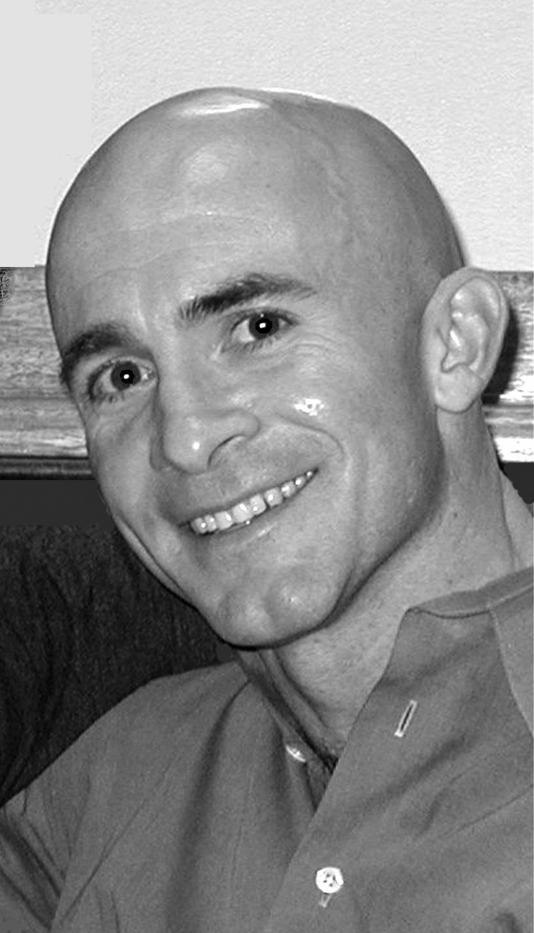

Author Bio:

Author Contacts:

Thank you to Scott D. Pomfret for stopping by with such an amazing post for our blog anniversary. I’ve always been big on folklore and all things Irish (my ancestors were Irish) so this made for a very entertaining read for me.

Thank you again for stopping by!

Yes, it’s one fabulous post. I love the mixture of reality/lore/storytelling.

Now to get you to read The Hunger Man, Cindi 🙂

So happy to be part of the celebration of the great work you do! Thank you for inviting me!

Anytime, Scott.